Metal doesn’t always mean hard. Some metals are so soft that they challenge everything we think we know about strength and durability. What is the softest metal on Earth, and why does it behave this way? In this guide, I break down the science, properties, and real uses of the softest metal you’ll find on the periodic table.

Get 20% offf

Your First Order

How Do We Define “Softness” in Metals

In engineering terms, metal softness is closely linked to malleability, yield strength, and plastic deformation. A soft metal requires minimal force to permanently change shape and has a low yield stress. This is why softness is often evaluated using indentation-based tests such as Brinell or Vickers rather than scratch-based scales alone.

From my experience working with different alloys, metals classified as “soft” typically show:

- Low hardness values (e.g., Mohs < 1)

- High ductility and malleability

- Easy machinability, often cut with a blade rather than tools

Using these criteria, softness becomes a measurable, comparable property—not a vague description. This framework clearly separates everyday soft metals like aluminum or copper from truly extreme cases such as cesium.

The Softest Solid Metal on Earth: Cesium

When scientists talk about the softest metal on Earth, cesium always comes up first. Its extreme softness, low melting point, and unusual atomic structure make it a fascinating outlier in the metal world—and a perfect case study for understanding what “soft” really means in materials science.

Cesium (Cs) is widely recognized as the softest solid metal at room temperature. It belongs to the alkali metal group (Group 1), alongside lithium, sodium, and potassium—but it stands out as the softest of them all.

From a measurable standpoint, cesium has a Mohs hardness of about 0.2, making it softer than talc (Mohs 1) and far softer than common metals like aluminum or copper. In practice, cesium can be easily cut with a knife, and its surface deforms under minimal pressure—clear signs of extremely weak metallic bonding.

One reason cesium is so soft lies in its atomic structure. Cesium atoms are very large, with their single valence electron located far from the nucleus. This results in weak metallic bonds, meaning the atoms do not hold tightly together. In my experience explaining material behavior to engineers, cesium is a textbook example of how atomic size directly affects macroscopic properties like hardness.

Another unusual trait is its low melting point of 28.5°C (83.3°F). Cesium can melt in a warm room or even in your hand (under controlled lab conditions), reinforcing just how loosely its atoms are bound. This softness and reactivity are also why cesium is never used structurally, but instead reserved for specialized scientific and industrial applications.

Physical and Chemical Properties of Cesium

Cesium stands out not only because it is the softest solid metal on Earth, but also due to its unique physical and chemical behavior. Understanding these properties explains why cesium behaves so differently from common structural metals—and why its applications are highly specialized.

Physical Properties of Cesium

From a physical standpoint, cesium is extremely unusual for a metal:

- Appearance: Silvery-gold, shiny when freshly cut, but tarnishes rapidly in air

- Density: ~1.9 g/cm³ at 20°C, relatively low compared to many metals

- Melting Point: 28.5°C (83.3°F), meaning cesium can melt near body temperature

- Hardness: Mohs hardness ≈ 0.2, softer than wax and easily cut with a knife

- Malleability: Can be easily deformed under minimal force due to weak metallic bonding

In practical terms, I’ve seen cesium described as “liquid-like” in controlled labs—something no one would ever expect from a metal.

Chemical Properties of Cesium

Chemically, cesium is one of the most reactive elements in the periodic table:

- Atomic Number: 55

- Electron Configuration: [Xe] 6s¹

- Valence Electrons: 1, leading to extremely weak attraction to the nucleus

- Electronegativity (Pauling): 0.7 (very low)

- First Ionization Energy: ~375.6 kJ/mol (one of the lowest among metals)

Because of this structure, cesium reacts violently with water, oxygen, and even trace moisture. It readily forms ionic compounds and must be stored in vacuum or inert atmospheres. In my experience, this extreme reactivity is the primary reason cesium is rarely seen outside laboratories or sealed industrial systems.

How Cesium Compares to Other Soft Metals

To truly understand why cesium is considered the softest solid metal on Earth, it helps to compare it with other well-known soft metals. By looking at softness, reactivity, and real-world usability side by side, the differences become clear—and practically important.

| Metal | Physical State at Room Temp | Relative Softness | Reactivity | Key Characteristics | Typical Uses |

| Cesium (Cs) | Solid (near melting point) | Softest solid metal | Extremely high | Mohs ≈ 0.2, can be cut with a knife, melts at 28.5°C | Atomic clocks, space technology, medical imaging |

| Potassium (K) | Solid | Very soft | Very high | Softer than sodium, harder than cesium | Fertilizers, chemical synthesis |

| Sodium (Na) | Solid | Soft | Very high | Easily cut, reacts violently with water | Sodium lamps, chemical processing |

| Lithium (Li) | Solid | Moderately soft | High | Lightest metal, harder than Na/K/Cs | Batteries, aerospace alloys |

| Gallium (Ga) | Solid / melts at ~30°C | Soft (when solid) | Low | Melts in hand, not very reactive | Semiconductors, electronics |

| Lead (Pb) | Solid | Soft (malleable) | Low | Heavy but easily deformed | Radiation shielding, batteries |

| Mercury (Hg) | Liquid | N/A (not solid) | Low | Liquid at room temp, flows instead of deforming | Thermometers, lab instruments |

How Soft Is “Soft” in Real-World Terms

When scientists call a metal “soft,” they don’t mean flexible like rubber—they mean easy to cut, dent, or deform under very low force. Translating lab data into everyday comparisons helps engineers and readers truly understand how extreme metal softness can be in practice.

What “Soft” Really Means in Daily Terms

In materials science, softness is closely tied to malleability and resistance to deformation. A soft metal can be shaped, sliced, or dented with minimal pressure—sometimes even by hand tools.

To make this tangible, consider these real-world comparisons:

Cesium

Cesium is so soft it can be cut with a knife and dented with light finger pressure. Its Mohs hardness is about 0.2, making it comparable to wax or firm soap. In controlled environments, cesium can even deform under its own weight.

Gold

Gold is widely known as a soft metal, with a Mohs hardness of 2.5–3. Jewelers regularly alloy gold with copper or silver because pure gold bends too easily for structural use. Still, gold is far harder than cesium.

Other Alkali Metals

Lithium, sodium, and potassium can also be sliced with a knife, but their softness increases down the periodic table. Lithium is the hardest, cesium the softest, following predictable atomic bonding trends.

From my experience studying material selection, cesium represents the extreme end of softness—so extreme that it’s never used structurally, only scientifically.

Why This Comparison Matters

Understanding softness in practical terms helps engineers avoid material misuse. A metal that feels “solid” may still be unsuitable for load-bearing or wear-critical applications if its softness is too high.

Industrial and Scientific Uses of Cesium

Although cesium is too soft and reactive for everyday manufacturing, it plays an irreplaceable role in high-precision science and advanced industries. From atomic clocks to space propulsion, cesium’s unique physical and chemical properties enable technologies where accuracy, stability, and performance are critical.

Atomic Clocks & Global Timekeeping

Cesium is the reference element for the international definition of a second. Cesium-133 atoms oscillate at exactly 9,192,631,770 cycles per second, enabling atomic clocks accurate to 1 second in over 15 million years. These clocks are essential for GPS, internet synchronization, and telecommunications.

Oil & Gas Drilling Fluids

Cesium formate brines are widely used in high-pressure, high-temperature oil and gas drilling. Their high density, low viscosity, and recyclability reduce borehole collapse while minimizing environmental impact compared to traditional drilling fluids.

Medical & Radiation Applications

Radioactive isotopes such as Cesium-137 are used in cancer radiotherapy and medical calibration equipment. In controlled environments, cesium-based sources deliver precise radiation doses for targeted treatment.

Space Technology & Ion Propulsion

Cesium’s low ionization energy makes it suitable for ion thrusters, where cesium ions generate thrust for spacecraft maneuvering. This technology supports long-duration missions with extremely high fuel efficiency.

Optical Glass & Sensors

Non-radioactive cesium compounds are added to specialty optical glass to improve clarity, refractive index, and infrared transmission, widely used in precision lenses, detectors, and scientific instruments.

Research & Advanced Physics

In laboratories, cesium is used in studies of quantum mechanics, atomic structure, vacuum tubes, magnetometers, and spectroscopy, thanks to its predictable atomic behavior and extreme softness.

Advantages and Limitations of Using Cesium

Cesium’s extreme softness and reactivity make it unique among metals. These same traits give it unmatched value in high-precision science—while also placing strict limits on where and how it can be used. Understanding both sides is essential before choosing cesium for any application.

Advantages of Using Cesium

Exceptional Atomic Precision

Cesium defines the SI second. Its atomic resonance frequency (9,192,631,770 Hz) enables atomic clocks accurate to about 1 second in 15 million years, forming the backbone of GPS, telecom networks, and internet synchronization.

High Reactivity for Specialized Applications

Because cesium ionizes easily, it is ideal for ion propulsion systems, photoelectric cells, vacuum tubes, and radiation detection equipment. In space technology, this reactivity translates directly into efficiency.

Superior Performance in Oil & Gas Drilling Fluids

Cesium formate brines offer high density with low viscosity, improving borehole stability while reducing environmental impact compared to conventional drilling fluids.

Optical and Scientific Value

Cesium compounds are used to improve optical glass clarity and are widely applied in physics, chemistry, and atomic research, where predictable electron behavior is critical.

Limitations of Using Cesium

Extreme Reactivity and Safety Risks

Cesium reacts violently with water and air, producing heat, hydrogen gas, and caustic hydroxides. It must be stored under inert oil or in sealed ampoules and handled only by trained professionals.

High Cost and Limited Availability

Cesium is rare, mainly extracted from pollucite. Its scarcity and complex handling make it uneconomical for general industrial use, restricting it to niche, high-value fields.

Toxicity and Health Concerns

Exposure to cesium compounds—especially radioactive isotopes like Cs-137—poses serious health risks. Strict safety protocols are required in medical and industrial environments.

Environmental and Regulatory Constraints

Cesium mining and radioactive isotope management are heavily regulated due to environmental sensitivity, limiting large-scale adoption.

Why Metal Softness Matters in Science and Engineering

Metal softness is not a weakness—it’s a functional advantage in many scientific and engineering applications. From electronics to advanced research, understanding why softness matters helps engineers select the right materials for performance, manufacturability, and reliability.

Why Softness Is Technically Important

In materials science, softness usually refers to low hardness, high malleability, and ease of deformation. These properties allow metals to be shaped, bonded, or integrated with other materials using lower force and energy. In engineering practice, this directly translates to better formability, tighter contact interfaces, and reduced processing stress.

Benefits of Soft Metals in Engineering

- Improved Formability: Soft metals can be rolled, stamped, or drawn into complex geometries with minimal cracking or springback.

- Enhanced Contact Performance: In electronics, soft metals such as gold deform microscopically to create stable, low-resistance electrical contacts.

- Alloy Design Flexibility: Soft metals are often added to alloys to improve machinability, ductility, or bonding behavior without sacrificing overall strength.

From my experience, adding small amounts of soft metals into harder systems often reduces tool wear and improves manufacturing yield.

Trade-Offs and Engineering Balance

Softness comes with limitations. Soft metals typically have lower load-bearing capacity and higher wear rates. For this reason, they are rarely used alone in structural roles. Engineers instead combine them with harder materials—through alloying, coatings, or layered designs—to balance softness with strength, durability, and safety.

In real-world engineering, softness is not an endpoint, but a parameter that must be carefully controlled.

Interesting Facts About the Softest Metal

Cesium isn’t just the softest solid metal on Earth—it’s one of the most unusual. From melting near room temperature to defining the second itself, cesium’s extreme properties make it both scientifically vital and surprisingly fascinating.

Discovered Through Light, Not Mining

Cesium was discovered in 1860 by Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff using flame spectroscopy. It was the first element identified purely by its spectral signature, marking a milestone in analytical chemistry.

Named After Its Blue Signature

The name “cesium” comes from the Latin word caesius, meaning sky blue. This refers to the intense blue lines it produces in its emission spectrum—still used today for precise identification.

Almost Melts in Your Hand

Cesium has a melting point of just 28.5°C (83.3°F). On a warm day, it can soften or melt near body temperature. In practice, I’ve only seen this demonstrated in sealed lab environments due to safety risks.

Defines the International Second

The SI second is defined by the oscillation frequency of cesium-133 atoms: 9,192,631,770 cycles per second. Cesium atomic clocks are accurate to about 1 second in 15 million years.

Soft Like Wax—but Extremely Dangerous

Cesium has a Mohs hardness of ~0.2 and can be cut with a knife, yet it reacts violently with water and air. This contrast makes it one of the softest but most hazardous metals known.

FAQs

What Are The Top 10 Softest Metals?

In my experience, softness is best compared using Mohs hardness and practical deformability. The top 10 softest metals (softest → harder) are: Cesium (~0.2 Mohs), Rubidium, Potassium, Sodium, Lithium, Lead (~1.5 Mohs), Tin (~1.8 Mohs), Gold (~2.5 Mohs), Silver (~2.5–3 Mohs), Aluminum (~2.75 Mohs). Alkali metals dominate the top due to weak metallic bonding, while post-transition metals like lead and tin remain soft but far more stable.

What Is The Softest Form Of Metal?

From a scientific standpoint, the softest solid metal is cesium, with a Mohs hardness of about 0.2, meaning it can be cut with a knife and deformed by light pressure. If I include non-solid states, mercury is technically “softer” because it is liquid at room temperature (−39 °C freezing point). However, in engineering and materials science, softness comparisons almost always refer to solid metals, making cesium the clear answer.

What Metal Is Soft Enough To Bite?

Realistically, lead is the metal most often described as “soft enough to bite.” Historically, people could leave tooth marks in lead due to its low yield strength (~18 MPa) and Mohs hardness of ~1.5. I must stress this is dangerous—lead is toxic. While cesium is far softer, it reacts violently with moisture, making any physical contact unsafe. Lead’s softness is mechanical, not chemical, which explains this reputation.

Why Is Cesium So Rare?

Cesium is rare because it does not exist freely in nature and is found mainly in the mineral pollucite, which is geographically limited. In my research, global cesium production is only a few tens of tons per year, compared to millions of tons of aluminum. Its extreme reactivity also makes extraction, storage, and transport costly. These factors—scarcity, complex processing, and safety requirements—drive cesium’s high price and limited availability.

What Type Of Metal Is Soft?

Soft metals are typically alkali metals (Group 1) and post-transition metals. Alkali metals like lithium, sodium, and cesium are soft because they have one valence electron, leading to weak metallic bonds. Post-transition metals such as lead, tin, and gold are soft due to their atomic structure and bonding characteristics. In my experience, softness correlates strongly with low hardness, high malleability, and low yield strength, not with density or weight.

Conclusion

In real manufacturing, ultra-soft metals like cesium may not be used for load-bearing structures, but they demand a much deeper level of process control, material understanding, and environmental management.

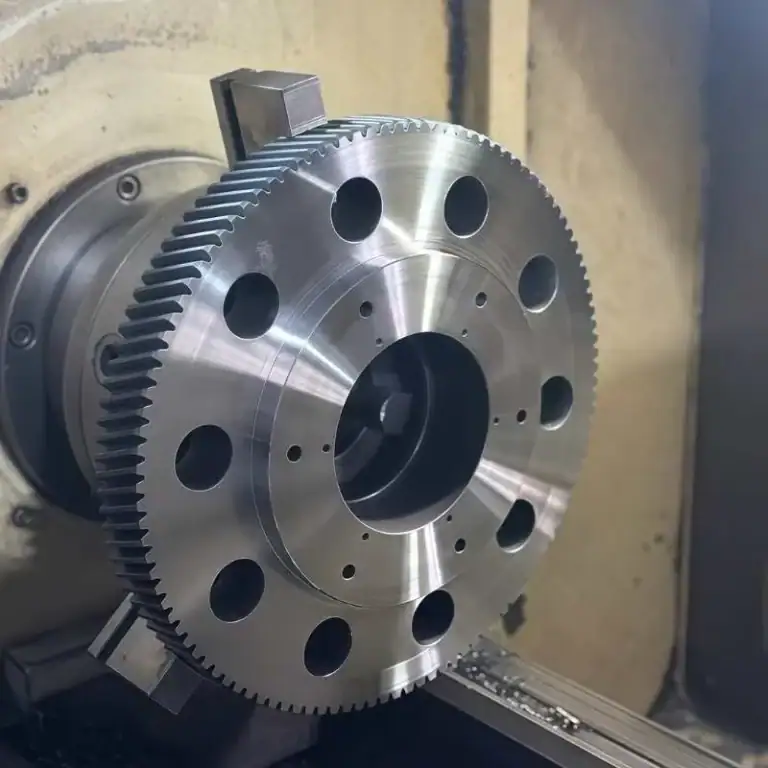

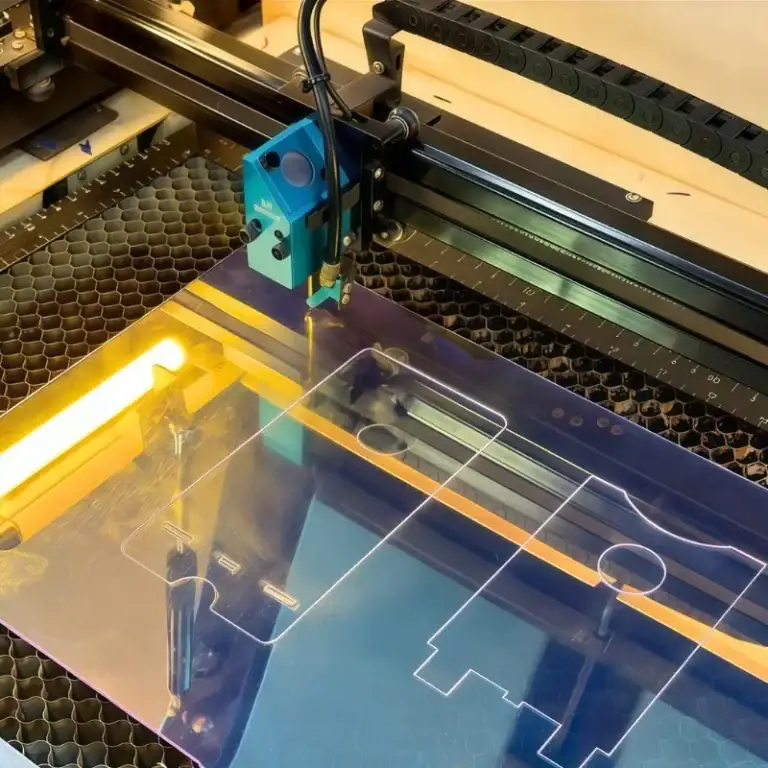

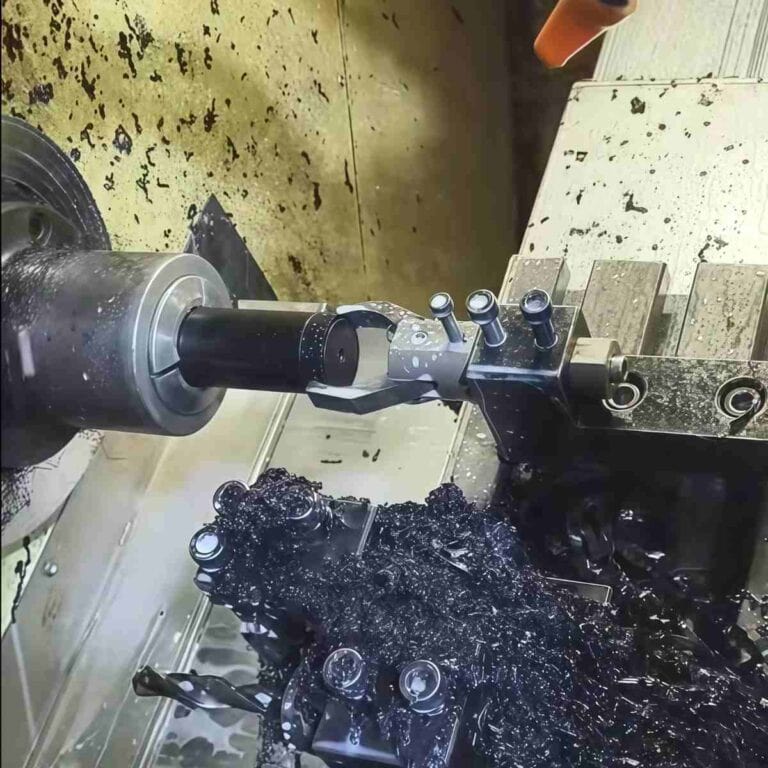

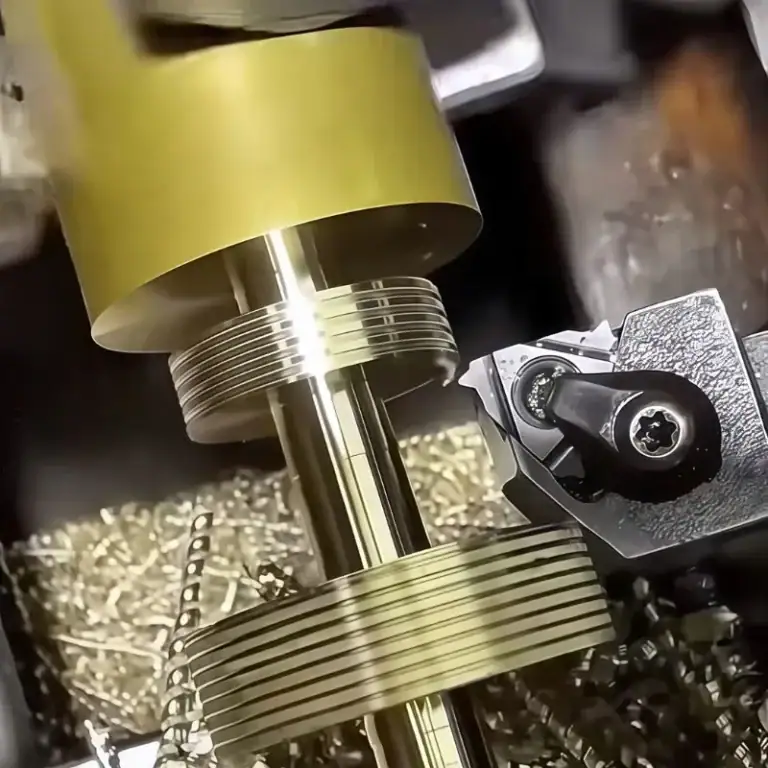

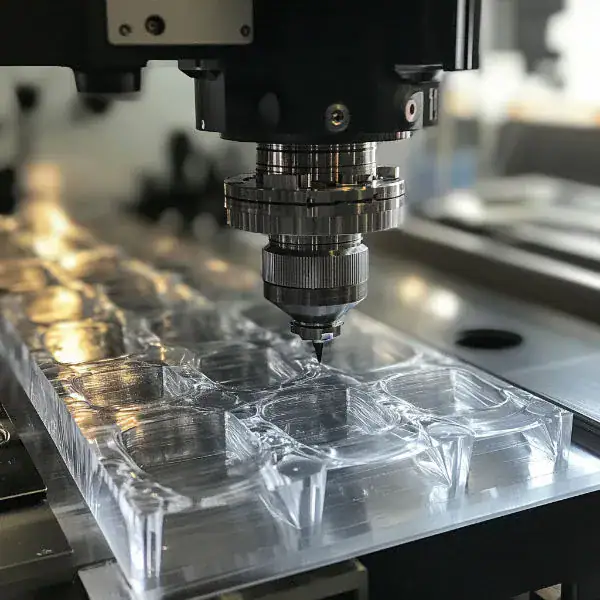

At TiRapid, we support precision CNC machining projects across the full material spectrum—from extremely soft metals to high-strength alloys—helping engineers evaluate machinability, tolerances, and real-world application limits. We believe true manufacturing advantage isn’t about how hard a material is, but how precisely its properties are understood and applied.