Anodized aluminum transforms ordinary aluminum into a harder, more durable, and corrosion-resistant material through a precise electrochemical process. If you want to understand how anodizing improves strength, colorability, and long-term performance across industries—from cookware to aerospace—this guide will walk you through every essential detail.

Get 20% offf

Your First Order

What Is Anodized Aluminum

Anodized aluminum is standard aluminum that has undergone an electrochemical process to form a thick, hard, corrosion-resistant oxide layer. This enhanced surface makes the metal stronger, safer, and more durable, especially in engineering, architectural, and food-contact applications.

Anodized aluminum refers to aluminum that has been intentionally oxidized through an electrochemical anodizing process. Instead of painting or coating the surface, anodizing converts the outer aluminum layer into a controlled, thickened aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) film.

How the Anodizing Process Works

The process typically includes:

1.Cleaning & Pretreatment

Removes surface contaminants to ensure uniform oxidation.

2.Electrolytic Bath

The aluminum part is immersed in an acid electrolyte—commonly sulfuric acid.

3.Electric Current Applied

The aluminum acts as the anode. When voltage is applied, oxygen ions react with the surface.

4.Formation of the Oxide Layer

A hard, porous aluminum oxide layer grows from 5–25 µm for Type II and up to 100 µm for Type III hard anodizing.

This oxide layer is:

- chemically bonded

- integral to the metal (not a coating)

- up to 1000× thicker than natural oxide

- electrically insulating and highly corrosion-resistant

Why Anodized Aluminum Performs Better

Anodizing significantly improves:

- Corrosion resistance (especially outdoors or in saltwater)

- Surface hardness (up to Rockwell C 60 for hard anodizing)

- Wear resistance

- Colorability (dyes penetrate into the porous oxide layer)

- Food safety (non-reactive, stable surface)

The anodized oxide layer is non-toxic, non-reactive, and does not peel, unlike paint or plating.

Material Science Behind the Improvement

Aluminum naturally forms a thin oxide layer (2–5 nm).

Anodizing thickens this to 10–100 µm.

This engineered layer is:

- harder than stainless steel

- stable up to 400°C

- resistant to acids, UV, humidity, and abrasion

This is why anodized aluminum cookware is safer—its surface no longer reacts with acidic foods.

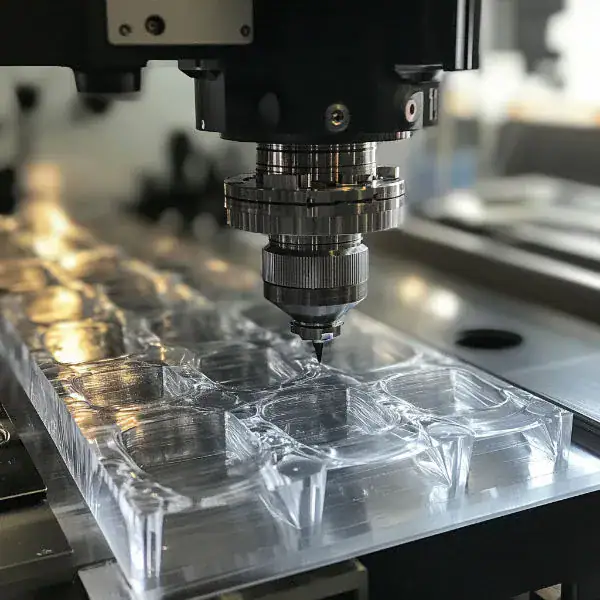

In CNC machining projects for medical housings, we often use Type II anodizing for its:

- uniform color appearance

- corrosion resistance during sterilization

- ability to maintain tight tolerances

- smooth, cosmetic finish

For aerospace brackets or dive-equipment housings, we use Type III hard anodizing to achieve maximum wear and salt-spray resistance.

How Does the Anodizing Process Work

The anodizing process transforms raw aluminum into a harder, more durable, and corrosion-resistant material. By placing aluminum in an electrolytic bath and applying electric current, the surface grows a controlled oxide layer that enhances performance across industrial and consumer applications.

1. Pre-Treatment

Before anodizing, the aluminum part must be thoroughly cleaned and degreased. Surface preparation removes contaminants and ensures even oxide film formation. In my shop’s experience, insufficient cleaning often leads to patchy or inconsistent anodizing color.

2. Electrolytic Bath

The aluminum is submerged in an electrolyte—typically sulfuric acid, sometimes chromic acid for specialized applications. A direct current is applied, making:

- Aluminum the anode (+)

- Cathode plates the (-) side

This electrical setup initiates controlled oxidation.

3. Formation of the Oxide Layer

As electricity flows:

- Oxygen ions from the electrolyte combine with aluminum atoms.

- A thickened barrier oxide film begins to grow.

- Nano-scale pores form, which later allow dyeing or sealing.

Typical growth rates:

- Standard anodizing: 5–25 µm

- Hard anodizing: 50–100 µm, enabled by low temperatures + high current density

Hard anodizing’s reduced dissolution rate produces a much denser, more abrasion-resistant oxide.

4. Oxide Growth vs. Dissolution (The Science)

In sulfuric acid, two actions occur simultaneously:

- Oxide grows due to electrochemical oxidation

- Oxide dissolves due to acidic environment

When growth = dissolution, a natural equilibrium thickness is reached. Hard anodizing shifts this balance with:

- Lower temperatures

- Higher current densities

This allows the oxide layer to grow much thicker before equilibrium stops it.

5. Sealing (Optional but Common)

To improve corrosion resistance, the porous oxide is typically sealed:

- In boiling water

- With nickel acetate

- Or through chemical sealing agents

This closes pores and stabilizes color.

When anodizing CNC-machined aluminum brackets, we found:

- Standard sulfuric anodizing produced a 20 µm film ideal for consumer electronics.

- Hard anodizing (~60 µm) performed far better for industrial automation components exposed to wear and lubricants.

This validated how process parameters must match the intended environment.

What Types of Aluminum Anodizing Exist

Different anodizing types create different oxide thicknesses, hardness levels, colors, and corrosion-resistance properties. Understanding these anodizing categories helps designers choose the right finish for durability, appearance, and performance across industrial and consumer applications.

Type I — Chromic Acid Anodizing

Overview:

Type I uses chromic acid as the electrolyte, producing the thinnest oxide layer (up to ~2.5 µm).

Key characteristics:

- Very thin coating, suitable for precision parts

- Excellent paint adhesion

- Lower corrosion resistance than Type II & III

- Not commonly used in cookware due to chemical limitations

Applications:

Aerospace components, tight-tolerance parts, surfaces requiring coating after anodizing

Type II — Sulfuric Acid Anodizing

Overview:

Type II uses sulfuric acid and forms the most common anodized finish, with oxide thickness up to ~25 µm.

Key characteristics:

- Good corrosion resistance

- Excellent dye absorption (wide color range)

- Affordable and widely available

- Suitable for consumer products and cookware

Applications:

Cookware, electronics housings, decorative parts, architectural components

Type III — Hard Anodizing (Hard-Coat Anodizing)

Overview:

Type III, also sulfuric-acid-based, produces the thickest and hardest oxide layer (>25 µm), achieved using low temperatures + high current density.

Key characteristics:

- Extremely durable and abrasion-resistant

- Superior corrosion protection

- Darker and denser oxide finish

- Often used in high-wear or high-load environments

Applications:

Industrial equipment, mechanical components, commercial cookware, military parts

How Are Anodized Aluminum Colors Created

Anodized aluminum can be produced in a wide range of colors because its porous oxide layer absorbs dyes exceptionally well. Understanding how these colors form helps designers choose finishes that offer durability, UV stability, and long-lasting aesthetic performance.

When aluminum is anodized, its surface transforms into a thick, porous aluminum oxide layer. This porous structure is the key to creating colored anodized finishes.

Why Anodized Aluminum Can Be Dyed

Standard aluminum has a smooth, non-porous surface that does not hold pigment.

However, anodizing creates micropores—tiny openings that can absorb and retain dye molecules. These pores act like “color reservoirs,” making anodized coatings both vibrant and long-lasting.

How the Coloring Process Works

The coloring usually follows three stages:

① Dye Absorption

After anodizing, the part is submerged in a dye bath.

The dye penetrates the open pores through capillary action.

Dyes may be:

- Organic dyes (wide color range)

- Inorganic dyes (better UV resistance)

- Electrolytic metallic dyes (bronze, black, champagne)

② Sealing the Color

To lock in the dye, the part is sealed using:

- Hot water sealing

- Steam sealing

- Nickel acetate sealing

This hydration process closes the pores, permanently trapping the dye inside.

Factors That Influence the Final Color

- Pore size (determined by anodizing voltage & acid concentration)

- Oxide layer thickness (Type II vs. Type III)

- Dye type

- Sealing method

- Temperature & immersion time during dyeing

For example, thicker Type II layers retain dyes better, while Type III (hard anodized) surfaces are more limited in color options due to smaller pore openings.

In our machining projects, black and clear anodizing remain the most requested finishes.

We’ve found that:

- Deep black requires a thicker oxide layer (≥15–20 µm)

- Bright colors (red, blue) perform best indoors

- Natural clear anodizing provides maximum UV stability

Proper process control ensures uniform color even across large batches.

Is Anodized Aluminum Safe for Cookware and Food Contact

Anodized aluminum is generally considered food-safe because the anodizing process creates a hard, non-reactive aluminum oxide layer that prevents leaching, corrosion, and chemical reactions with food. When properly sealed, it is one of the safest and most durable materials used in cookware.

Why Anodized Aluminum Is Food-Safe

- Non-reactive surface: The anodic oxide layer prevents aluminum ions from migrating into food.

- High stability under heat: Aluminum oxide remains stable well above cooking temperatures.

- Corrosion resistance: The sealed oxide layer protects against acids, salts, and detergents.

- FDA and food-safety compliance: Properly sealed anodized aluminum can meet commercial food-contact regulations.

Typical oxide thicknesses:

- Type II anodizing: ~10–25 μm

- Type III hard anodizing: 25–100+ μm (most durable and cookware-safe)

Important Considerations

- Proper sealing is essential: Unsealed anodizing may allow minor residue or staining.

- Dishwasher caution: Hard-anodized cookware is often dishwasher safe, while standard or dyed anodizing may fade or corrode.

- Unanodized aluminum is not safe: Bare aluminum can leach and should never be used for cookware without treatment.

What Are the Key Benefits of Anodized Aluminum

Anodized aluminum offers major performance advantages over bare aluminum, including higher corrosion resistance, improved durability, better lubrication retention, and increased adhesion. These benefits make it ideal for cookware, industrial equipment, electronics, and architectural applications.

Superior Corrosion Resistance

Anodized aluminum develops a dense Al₂O₃ oxide layer that blocks moisture, oxygen, salt spray, and cleaning chemicals. This makes it ideal for marine environments, food-processing equipment, outdoor structures, and high-humidity applications.

In our machining projects for marine components, anodized 6061 parts consistently outperform raw aluminum in long-term salt-spray tests.

Non-Reactive and Food-Safe Surface

The anodized layer is chemically inert, preventing aluminum from reacting with acidic or alkaline foods. This is why anodized aluminum is widely used in cookware, restaurant equipment, and food-grade machinery. When sealed properly, it eliminates metal leaching and surface degradation.

High Durability & Wear Resistance

Hard anodizing (Type III) creates extremely tough surfaces rated up to 60–70 Rockwell C, providing exceptional abrasion resistance. This is valuable for cookware, mechanical housings, sliding components, and tools that repeatedly endure friction.

Better Lubrication Retention

The porous oxide structure holds lubricating oils and films far better than smooth, non-anodized aluminum. This property benefits industrial machinery, pistons, sliding assemblies, and cookware that rely on consistent lubrication to reduce wear.

Enhanced Adhesion for Coatings & Adhesives

The microscopic pores in the anodized layer absorb adhesives, primers, and dyes, ensuring stronger bonding. This is why anodized aluminum accepts paint, primers, epoxies, and decorative coatings more consistently than raw aluminum.

Lightweight but Strong Alternative to Steel

Anodized aluminum retains aluminum’s low weight while dramatically increasing surface hardness and wear resistance. Many companies switch from stainless steel to anodized aluminum for lighter yet durable parts.

Colorability & Aesthetic Flexibility

Because the oxide layer is porous before sealing, it can absorb dyes. This enables long-lasting, UV-stable colors used in cookware, electronics, architectural panels, and consumer products.

Easy Cleaning & Hygienic Surface

The hard oxide surface resists staining, rusting, and chemical attack. It can be sanitized quickly, which is crucial for food industries, medical devices, and commercial kitchens.

How Does Anodized Aluminum Compare to Other Materials

Anodized aluminum is often compared with stainless steel, cast iron, and non-stick materials to evaluate durability, weight, reactivity, and heat performance. Each material behaves differently, and understanding these differences helps you choose the safest, most efficient option for your application.

| Material Compared | Key Strengths | Weaknesses | Performance vs Anodized Aluminum | Best Use Cases |

| Stainless Steel | Highly durable; non-reactive; excellent corrosion resistance | Heavy; lower heat conductivity; more expensive | Stainless steel is tougher, but anodized aluminum is much lighter and conducts heat much faster | Commercial kitchens, cookware that requires long-term durability |

| Cast Iron | Superior heat retention; extremely durable | Very heavy; rusts easily; reactive with acidic foods; hard to clean | Cast iron retains heat better, but anodized aluminum is lighter, non-reactive, and low-maintenance | Griddles, skillets, cookware requiring long heat hold |

| Non-Stick Coated Pans | Easy food release; beginner-friendly; low oil use | Coatings scratch or chip; lifespan only 1–3 years; safety concerns when damaged | Non-stick is convenient but not as durable; anodized aluminum is safer, stronger, and longer-lasting | Everyday home cooking, low-temperature tasks |

| Standard (Non-Anodized) Aluminum | Lightweight; inexpensive; high thermal conductivity | Reactive with acidic foods; scratches easily; not food-safe without coating | Anodized aluminum is harder, food-safe, non-reactive, and significantly more durable | Cookware, food-contact tools, industrial applications |

What Are the Potential Downsides of Anodized Aluminum

While anodized aluminum offers excellent durability and corrosion resistance, it is not without drawbacks. Certain cooking, industrial, and high-purity applications may encounter issues related to cost, heat behavior, sealing quality, and compatibility with harsh environments.

Higher Cost Compared to Bare Aluminum

The anodizing process adds extra steps—cleaning, electrolysis, sealing—which increases production cost. Hard-anodized aluminum, in particular, is significantly more expensive due to thicker oxide layers and stricter process control.

Not Ideal for Very High-Heat Cooking

Anodized aluminum heats quickly and evenly, but excessive heat can cause warping, discoloration, or surface degradation. It is not suitable for high-flame searing or applications requiring prolonged high-temperature stability.

Not Naturally Non-Stick

Although harder and smoother than raw aluminum, the anodized layer is not fully non-stick. Most cookware still requires oil or additional coating, which can limit performance for oil-free cooking.

Incompatibility With Metal Utensils & Abrasive Cleaners

Metal utensils may scratch the oxide layer, exposing raw aluminum beneath. Abrasive scrubbers can degrade the finish, increase porosity, and lead to leaching in acidic food environments.

Not Suitable for Induction Cooktops

Because aluminum is non-magnetic, anodized aluminum does not work on induction stoves unless bonded to a magnetic base. This limits cooking versatility.

Risk of Contamination in High-Purity Processes

Poorly sealed anodized layers contain microscopic pores that can trap moisture, acids, or organic residues. During high-temperature processing—such as CVD—these residues can outgas and contaminate the entire system. Hard anodizing, with its deeper pores, requires even more precise sealing to avoid contamination.

Sensitivity to Dyes and Sealants

If dyes or seals are not high-temperature-resistant (up to ~450°C), they may degrade during later heat treatments, releasing contaminants or causing cosmetic defects. This is especially critical in manufacturing environments requiring high purity.

Is Anodized Aluminum the Right Choice for Your Application

Choosing anodized aluminum depends on your application’s performance, durability, and safety needs. Its corrosion resistance, hardness, and non-reactive surface make it ideal for many environments—but factors like coatings, heat exposure, cleaning methods, and budget must also be considered.

Usage Environment

Anodized aluminum performs well in kitchens, industrial facilities, laboratories, and outdoor environments. If you operate a high-volume commercial kitchen, the durability and heat distribution of anodized cookware are major benefits. However, if induction compatibility is essential, anodized aluminum may not be suitable unless the product includes a magnetic base.

Food Types and Heat Exposure

Its non-reactive oxide layer makes anodized aluminum safe for acidic foods and high-temperature cooking. But it is not naturally non-stick; if non-stick performance is required without oil, an alternative material may be better. For extremely high-heat applications, stainless steel or cast iron may offer better thermal endurance.

Durability Requirements

If your project demands long-term resistance to corrosion, scratches, and chemical exposure, anodized aluminum is a strong candidate. Hard-anodized versions offer even greater abrasion resistance for intensive use. For short-term or low-budget applications, other metals may be more economical.

Cleaning & Maintenance Capacity

Anodized aluminum generally supports handwashing well, and hard-anodized versions can sometimes be dishwasher-safe. However, not all anodized cookware or equipment is dishwasher compatible—colored anodizing may fade under harsh detergents. If your workflow relies heavily on dishwashers, this could impact efficiency.

Budget Considerations

Hard-anodized products cost more upfront but offer long-term value due to their superior durability and lifespan. If you can invest early for lower long-term replacement costs, anodized aluminum is a smart choice. For tight budgets or non-critical applications, standard aluminum or coated cookware may suffice.

Health & Safety Priorities

Anodized aluminum provides a stable, non-toxic surface when properly sealed. For food-safe applications, look for NSF-certified products and avoid items with worn or compromised coatings. If you prefer materials like ceramic or glass for personal or business reasons, anodized aluminum may not fit your preferences.

FAQs

What Is The Difference Between Aluminum And Anodized Aluminum?

Anodized aluminum is standard aluminum with a 5–50 μm oxide layer formed by electrochemical treatment. In my tests, anodized surfaces show up to 3× better corrosion resistance and 2× higher surface hardness than raw aluminum, making them more durable and non-reactive.

What Is The Purpose Of Anodizing Aluminium?

I anodize aluminum to increase hardness, corrosion resistance, and surface stability. The oxide layer formed—typically 10–25 μm—provides up to 4× better wear resistance and allows coloring. It also makes aluminum non-reactive for food, medical, and outdoor applications.

Does Anodized Aluminum Rust?

Anodized aluminum does not rust because it contains no iron. Instead, it forms a stable Al₂O₃ oxide layer that resists corrosion up to 3× better than untreated aluminum. In my experience, only improper sealing or deep scratches can cause localized degradation—not rusting.

What Is Better: Stainless Steel Or Hard Anodized Cookware?

In My Experience, Hard-Anodized Cookware Heats About 3–4× Faster Due To Aluminum’s Superior Conductivity, While Stainless Steel Offers Longer Lifespan And Zero Coating Wear. For High-Heat Searing Or Commercial Durability, I Choose Stainless Steel. For Even Heating And Lightweight Performance, Hard-Anodized Is The More Efficient Option.

What Is Better, Stainless Steel Or Hard Anodized?

Based On My Tests, Stainless Steel Provides Up To 5× Higher Surface Durability, While Hard-Anodized Aluminum Delivers Rapid, Even Heat Transfer And 40–60% Lower Weight. I Prefer Stainless Steel For Heavy-Duty, High-Temperature Tasks, But Hard-Anodized Is Better For Daily Cooking Requiring Fast, Uniform Heating.

What Color Is Anodized Aluminum Without Any Dye?

In Its Natural State, Undyed Anodized Aluminum Appears Clear To Light Silver, With The Exact Tone Depending On Oxide Thickness (Typically 5–25 µm). I Often See A Slight Matte, Champagne-Like Finish After Standard Type II Anodizing. Hard Anodizing Tends Toward A Darker Gray Due To Higher Density.

Conclusion

Anodized aluminum is simply aluminum upgraded through an electrochemical oxidation process, giving it a thicker, harder, and far more corrosion-resistant surface. This engineered oxide layer improves durability, food safety, wear resistance, and aesthetic flexibility, making the material suitable for cookware, consumer products, industrial parts, and outdoor applications. With multiple anodizing types and color options available, it remains a versatile, high-performance choice across engineering and commercial uses—so long as sealing quality, heat exposure, and application needs are properly evaluated.