Machining is a core part of modern manufacturing, used to transform raw materials into precise parts. But how many types of machining processes actually exist? This guide breaks down the main machining categories and operations to help you quickly understand your options and choose the right process.

Get 20% offf

Your First Order

What Is Machining?

Machining is a core manufacturing method used to transform raw materials into accurate, functional components. By precisely removing unwanted material, it achieves high precision, tight tolerances, and consistent performance across many industries.

As a subtractive manufacturing process, machining shapes a solid workpiece by cutting away material to reach the required geometry, dimensions, and surface finish. The initial stock—such as bars, plates, castings, or forgings—is always larger than the finished part.

Material is removed using cutting tools, abrasive wheels, or other controlled techniques. Common machining processes include turning, milling, drilling, and grinding, each selected to meet specific design, accuracy, and tolerance needs.

Why Machining Matters in Manufacturing?

Machining plays a critical role in manufacturing by turning raw materials into precise, functional components. Its ability to control dimensions, surface quality, and consistency makes it essential for modern industrial production.

The primary purpose of machining is to produce parts with defined geometry, tight tolerances, and reliable surface finishes that meet engineering and functional requirements. By precisely removing excess material, machining enables manufacturers to achieve accurate shapes, holes, threads, and complex features.

One of machining’s greatest strengths is dimensional accuracy. CNC machining routinely achieves tolerances of ±0.01mm or tighter, which is critical for assemblies requiring exact fits and interchangeability. In my experience, this level of precision is difficult to match with forming or additive processes alone.

Machining also plays a key role in surface finishing. Processes such as milling and grinding reduce surface roughness, improving wear resistance, fatigue life, and visual quality. From a cost perspective, machining is especially efficient for low- to medium-volume production and custom parts, where tooling for molding or casting would be prohibitively expensive.

Finally, machining integrates seamlessly with other manufacturing methods. Cast, forged, or 3D-printed parts are often machined afterward to achieve final accuracy, making machining indispensable across the entire production chain.

Main Types of Machining Processes

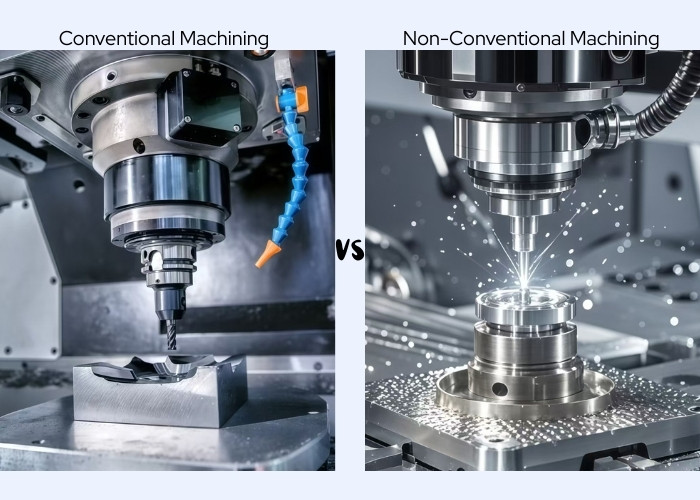

Machining processes can be broadly classified into conventional (traditional) machining and non-conventional machining. The key difference lies in whether material is removed through direct mechanical contact or by thermal, chemical, or electrical energy. Understanding these categories helps engineers choose the most cost-effective and technically suitable process for precision, material type, and geometry.

Conventional Machining Processes

Conventional machining relies on physical cutting tools that directly contact the workpiece to remove material. These processes are widely used due to their versatility, controllability, and compatibility with CNC automation.

Turning

Turning is performed on a lathe where the workpiece rotates while a single-point cutting tool removes material. It is ideal for producing cylindrical, conical, and rotational parts such as shafts, bushings, threaded components, and bearing seats.

From my experience, CNC turning delivers excellent roundness and surface finish, especially for high-volume production with tight concentricity requirements.

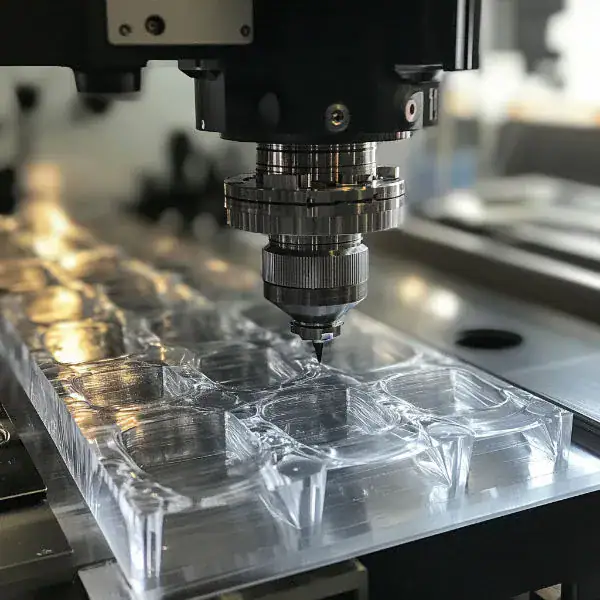

Milling

Milling uses rotating multi-point cutting tools while the workpiece remains fixed. It supports complex operations such as slotting, pocketing, contouring, and 3D surface machining.

With 3-axis to 5-axis CNC milling, manufacturers can achieve complex geometries and tolerances down to ±0.01mm, reducing setups and improving overall accuracy.

Drilling, Boring, and Reaming

- Drilling creates initial holes using multi-point drill bits.

- Boring enlarges and corrects hole alignment after drilling.

- Reaming refines hole size and surface finish for precision fits.

These operations are critical for assemblies where hole accuracy directly affects part performance and alignment.

Grinding

Grinding is a precision finishing process using abrasive wheels to achieve tight tolerances and superior surface quality. It is commonly used when dimensional accuracy must reach microns, such as in tooling, aerospace components, and bearing surfaces.

Broaching

Broaching uses a toothed tool to remove material in a single linear pass, making it highly efficient for producing keyways, splines, internal profiles, and gear features. Although tooling costs are higher, broaching is extremely cost-effective for mass production.

Non-Conventional Machining Processes

Non-conventional machining removes material without direct tool contact, making it suitable for hard, brittle, heat-sensitive, or complex materials that are difficult to machine conventionally.

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)

EDM removes material through controlled electrical sparks. It is ideal for hardened steels, molds, dies, and intricate cavities, achieving extremely tight tolerances without inducing mechanical stress.

Laser Beam Machining (LBM)

LBM uses a focused laser to melt or vaporize material. It enables high-speed cutting, micro-holes, engraving, and complex contours, especially in thin metals and precision components.

Electrochemical Machining (ECM)

ECM removes material through electrochemical dissolution. Since there is no tool wear or heat-affected zone, it is well suited for turbine blades, deep cavities, and superalloys in mass production.

Abrasive & Water Jet Machining

These processes use high-velocity abrasive streams (with air or water) to cut material. They generate minimal heat and distortion, making them ideal for composites, plastics, glass, and heat-sensitive metals.

Ultrasonic & Micro-Machining

Used for micro-scale features and brittle materials, these methods enable precision manufacturing in electronics, medical devices, and optical components where conventional tools fail.

Conventional vs Non-Conventional Machining: Key Differences

Choosing between conventional and non-conventional machining directly affects precision, cost, and part performance. The table below highlights the key differences to help you select the most suitable machining method for your application.

| Comparison Factor | Conventional Machining | Non-Conventional Machining |

| Material Removal Method | Direct mechanical cutting with physical tool contact | Material removal via electrical, thermal, chemical, or fluid energy |

| Typical Processes | Turning, Milling, Drilling, Grinding, Tapping | EDM, Laser Cutting, Waterjet, ECM, Ultrasonic Machining |

| Suitable Materials | Aluminum, mild steel, brass, plastics | Hardened steel, superalloys, titanium, ceramics, composites |

| Hard-to-Machine Materials | Limited, high tool wear | Excellent capability, minimal tool wear |

| Precision Capability | High (±0.01–0.02mm typical) | Very high (micron-level achievable) |

| Surface Finish Quality | Good to excellent, may require secondary finishing | Excellent, often no secondary finishing needed |

| Complex Geometry Handling | Limited by tool access and shape | Ideal for complex, deep, or internal features |

| Material Removal Rate | High, efficient for bulk removal | Lower, focused on accuracy over speed |

| Tool Wear | Present and unavoidable | Minimal or none (non-contact processes) |

| Initial Equipment Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Production Cost Efficiency | Best for small to medium complexity parts | Best for high-precision or special materials |

| Typical Use Cases | Structural parts, housings, brackets, shafts | Mold inserts, medical devices, aerospace components |

| Best Application Stage | Prototyping, rough machining, volume production | Precision features, finishing, difficult geometries |

Which Machining Process Is Most Accurate?

Accuracy is often the deciding factor in machining process selection. From aerospace to medical devices, even micron-level deviations can affect performance. Understanding which machining process delivers the highest accuracy helps engineers reduce risk and optimize results.

From my experience, non-conventional machining processes consistently achieve the highest accuracy due to their non-contact or energy-based material removal mechanisms.

Processes such as EDM, Laser Beam Machining (LBM), Electron Beam Machining (EBM), and Electrochemical Machining (ECM) operate with cutting mediums smaller than a human hair—often below 0.01mm, and in some cases reaching micron-level precision.

Because there is no physical cutting tool, these processes eliminate tool deflection, vibration, and mechanical wear—common accuracy-limiting factors in conventional machining. This makes them ideal for hard materials, micro-features, sharp internal corners, and complex geometries.

That said, precision CNC machining (including high-end milling, turning, and grinding) can still achieve tolerances of ±0.005mm to ±0.001mm when process control, tooling, and fixturing are optimized. In real production, I often see the best results achieved by combining precision CNC machining with non-conventional finishing processes.

Applications of Different Machining Processes

Different machining processes exist because no single method fits every application. From simple holes to micron-level features, each machining process serves a specific purpose. Understanding where each process performs best helps reduce cost, improve quality, and speed up production.

In real manufacturing projects, machining processes are selected based on geometry complexity, tolerance requirements, material type, and production volume.

Turning & Facing

Turning is ideal for rotational parts such as shafts, bushings, pins, and threaded components. I often see it used for engine parts and mechanical assemblies where concentricity and roundness are critical.

Milling

Milling dominates applications involving slots, pockets, contours, and complex 3D geometries, including molds, housings, and brackets. Multi-axis CNC milling is especially effective for aerospace and automation components.

Drilling, Boring & Reaming

These processes are essential for precision hole-making. Drilling creates holes, boring improves concentricity, and reaming achieves tight tolerances—commonly required in automotive, aerospace, and medical assemblies.

Grinding & Lapping

When surface finish and accuracy are critical, grinding and lapping are applied. These processes are widely used for bearings, sealing surfaces, cutting tools, and precision components requiring micron-level finishes.

Broaching & Knurling

Broaching is ideal for keyways, splines, and internal profiles in high-volume production, while knurling is commonly used to improve grip on handles, knobs, and fasteners.

Precision & Micro Machining

For parts requiring tolerances below ±0.005mm or micro-scale features, precision machining and micro machining are essential. I frequently see these applied in medical devices, electronics, optics, and aerospace sensors.

Non-Conventional Machining (EDM, Laser, Waterjet, ECM)

These processes excel at machining hard, brittle, heat-sensitive, or complex materials. Applications include molds, turbine blades, surgical tools, and thin-walled structures, where traditional cutting tools struggle.

From my experience, the most successful projects often combine conventional machining for efficiency with non-conventional or precision processes for critical features.

FAQs

How Are Machining Processes Selected For Different Materials?

I select machining processes based on material hardness, machinability, and thermal sensitivity. Aluminum and mild steel work well with turning and milling, while hardened steels favor grinding or EDM. Brittle materials like ceramics or glass require ultrasonic or laser machining. Proper selection can reduce tool wear by 30–50% and improve part consistency.

Why Are Multiple Machining Processes Often Used On One Part?

In real manufacturing, I rarely use just one machining process. A part may be milled for shape, drilled and reamed for holes, then ground or lapped for final accuracy. Combining processes balances speed, cost, and precision, often reducing overall production time by 20–40% while ensuring tight tolerances.

How Do Machining Processes Impact Manufacturing Cost?

From my experience, machining cost is heavily influenced by process selection. Conventional machining such as turning and milling offers the lowest cost for medium to high volumes, while non-conventional methods like EDM or laser machining can increase unit cost by 20–60% due to energy consumption and equipment investment. However, for complex or hard materials, these advanced processes often reduce rework and scrap, lowering total project cost.

What Machining Processes Are Best For Complex Geometries?

When dealing with complex geometries, I often combine CNC milling, 5-axis machining, and non-conventional processes. Five-axis CNC can machine multi-face features in one setup, reducing alignment errors by over 50%. For sharp internal corners or deep cavities, EDM and laser machining outperform conventional tools, especially in mold, aerospace, and medical applications.

How Do CNC Machining Processes Improve Production Efficiency?

In my projects, CNC machining significantly improves efficiency through automation and repeatability. Compared to manual machining, CNC processes can increase productivity by 2–4 times, while maintaining consistent tolerances. Multi-axis CNC further reduces setup time and human error, making it ideal for both prototyping and batch production.

Conclusion

Machining shapes raw materials into precise parts through controlled material removal. By combining conventional machining for efficiency with non-conventional, precision, and micro-machining for complex features and tight tolerances, manufacturers achieve the best balance of accuracy, cost, and performance across industries.