From skyscrapers to spacecraft, metal strength defines what modern engineering can achieve. This guide ranks the top 10 strongest metals in the world, explains how metal strength is measured—such as tensile strength, yield strength, and hardness—and highlights where each strong metal performs best in real industrial applications.

Get 20% offf

Your First Order

What Makes a Metal Strong

Metal strength isn’t defined by a single number. In engineering, it’s a combination of how a metal resists force, deformation, heat, and failure. Understanding these factors helps engineers choose materials that perform reliably in real-world applications.

From an engineering perspective, metal strength is determined by several measurable factors:

- Hardness: Resistance to scratching and indentation, often measured by Rockwell or Vickers tests.

- Yield Strength: The stress level where permanent deformation begins.

- Tensile Strength: The maximum pulling force a metal can withstand before breaking.

- Young’s Modulus: Indicates stiffness—how much a metal bends under load.

- Melting Point: Higher melting points usually correlate with better high-temperature strength.

In practice, I’ve found that no single metric works alone. Strong metals are selected based on how these properties interact under real service conditions.

Top 10 Strongest Metals in the World (Ranked)

When engineers talk about the strongest metals, they rarely mean just one property. Strength depends on tensile load, heat resistance, density, and real-world reliability. Below, I rank the top 10 strongest metals based on engineering performance and industrial relevance.

| Rank | Metal | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Melting Point (°C) |

| 1 | Tungsten | ~1,510 | 3,422 |

| 2 | Maraging Steel | 1,900–2,400 | ~1,410 |

| 3 | Titanium (Alloy) | ~430–1,100 | 1,668 |

| 4 | Inconel (Nickel Alloy) | ~1,000–1,400 | ~1,350 |

| 5 | Chromium | ~418 | 1,907 |

| 6 | Vanadium | ~800 | 1,910 |

| 7 | Rhenium | ~1,000 | 3,180 |

| 8 | Tantalum | ~750 | 3,017 |

| 9 | Zirconium | ~330 | 1,855 |

| 10 | Lutetium | ~700 | 1,663 |

In my experience, no single metal dominates all applications—context defines true strength.

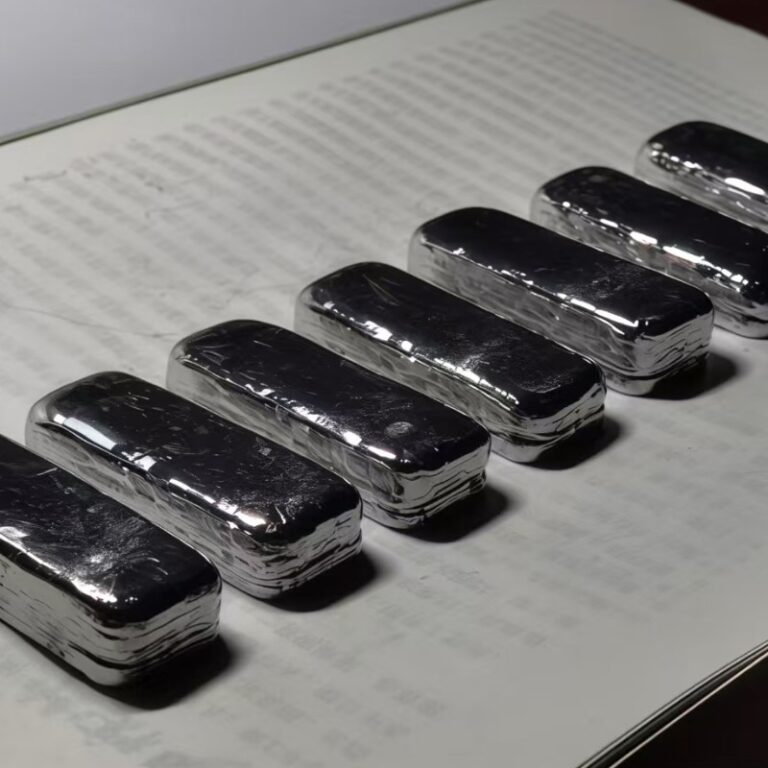

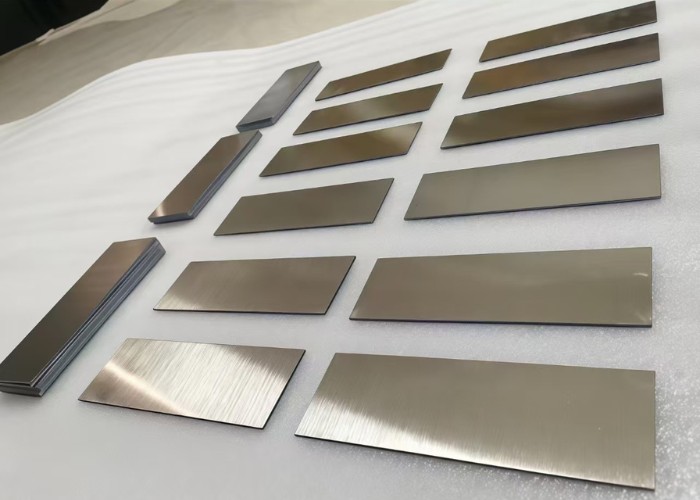

Pure Metals vs Alloys: Why Alloys Are Stronger

In materials engineering, strength rarely comes from purity. While pure metals offer predictable properties, alloys dominate real-world applications. Understanding why alloys outperform pure metals is key to selecting materials for high-stress, high-temperature, and long-life applications.

From an engineering perspective, pure metals such as iron, aluminum, or titanium have uniform atomic structures. This uniformity makes them easier to study—but also easier to deform. Under load, atoms in pure metals can slide past each other along crystal planes, leading to lower yield strength and faster plastic deformation.

Alloys solve this limitation through controlled disruption of the crystal lattice. By introducing alloying elements (such as carbon, chromium, nickel, or vanadium), atomic spacing becomes irregular. This impedes dislocation movement—the primary mechanism of metal deformation—resulting in significantly higher strength and hardness.

For example, pure iron is relatively soft and prone to corrosion, while stainless steel (iron + chromium + nickel) achieves much higher yield strength and corrosion resistance. Similarly, pure nickel loses strength at high temperatures, but nickel-based alloys like Inconel retain mechanical integrity above 700°C.

In my experience, alloys are chosen not just for higher strength, but for stability under real operating conditions—heat, stress, corrosion, and fatigue—where pure metals often fail prematurely.

Key Properties That Drive Metal Strength

Metal strength is not defined by a single number. In engineering practice, strength is a combination of multiple mechanical properties that determine how a metal behaves under real loads, heat, and impact. Understanding these properties is essential for safe and efficient material selection.

In materials engineering, metal strength is evaluated through several key properties, each serving a different design purpose:

Tensile Strength

Measures resistance to pulling forces. High tensile strength metals, such as tungsten (>1,500 MPa), are used in aerospace, cables, and high-load structures.

Compressive Strength

Indicates how well a metal resists crushing loads. Materials like tungsten carbide and chromium alloys excel in tooling, drilling, and structural support.

Yield Strength

Defines the stress point where permanent deformation begins. Stainless steel’s high yield strength makes it ideal for pressure vessels and pipelines.

Impact Strength

Represents the ability to absorb sudden energy without fracturing. Titanium alloys perform exceptionally well here, making them suitable for aerospace and defense systems.

From my engineering experience, selecting metals based on only one strength metric often leads to premature failure. Balanced evaluation is the key.

Industrial Applications of the Strongest Metals

The strongest metals are not chosen by name, but by performance. In aerospace, construction, and medical industries, strength, heat resistance, and reliability determine material selection. This section explains where the strongest metals truly deliver value—and why.

Aerospace Engineering

Aerospace applications demand extreme strength-to-weight ratios and thermal stability.

- Titanium alloys combine high tensile strength with low density, reducing aircraft weight while maintaining structural integrity.

- Nickel-based superalloys retain strength above 800–1,000°C, making them essential for turbine blades and jet engines.

From my experience, material failure in aerospace is rarely due to peak load—it’s usually heat fatigue or creep, where these alloys excel.

Construction & Infrastructure

Construction prioritizes load-bearing capacity, yield strength, and long-term durability.

- Structural steel remains the backbone of bridges and high-rise buildings due to predictable strength and cost efficiency.

- Advanced high-strength steels (AHSS) improve seismic resistance while reducing material volume.

Here, “strongest” means safe deformation before failure, not maximum hardness.

Medical Devices & Implants

Medical applications require strength with absolute reliability.

- Titanium dominates implants due to its biocompatibility and fatigue resistance.

- Stainless steel is widely used in surgical tools for its yield strength and corrosion resistance.

In regulated industries, consistency and certification matter as much as raw strength data.

FAQs

What Are The Big 4 Heavy Metals

I Define The “Big 4 Heavy Metals” As Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Cadmium (Cd), And Chromium (Cr). These Metals Have High Atomic Weights And Densities Typically Above 7 g/cm³. From An Engineering And Environmental Perspective, They Are Noted For Toxicity Rather Than Structural Strength. Lead Is Dense (11.34 g/cm³), Mercury Is Liquid At Room Temperature, Cadmium Accumulates In Biological Systems, And Hexavalent Chromium Is Highly Hazardous In Industrial Use.

What Metal Is Hardest To Break

From An Engineering Standpoint, Tungsten Is The Hardest Metal To Break Under Extreme Conditions. It Has A Tensile Strength Around 1,510 MPa And The Highest Melting Point Of Any Metal At 3,422°C. While It Is Brittle Under Impact, Its Resistance To Heat, Deformation, And Tensile Failure Makes It Exceptionally Difficult To Break In High-Temperature Or High-Load Applications Such As Cutting Tools, Rocket Nozzles, And Furnace Components.

What Is The King Of All Metals

In Engineering, There Is No Absolute “King,” But I Often Refer To Steel As The King Of Metals In Real-World Use. Modern Steels Can Reach Tensile Strengths Above 2,000 MPa, Are Cost-Effective, Highly Available, And Easily Alloyed. Steel Dominates Construction, Transportation, Energy, And Manufacturing. While Other Metals Outperform Steel In Specific Metrics, No Metal Matches Steel’s Overall Balance Of Strength, Versatility, And Scalability.

Are Stronger Metals Always Heavier?

No—stronger metals are not always heavier. Strength and density are independent properties. For example, tungsten is extremely strong but also very dense (~19.3 g/cm³), while titanium alloys deliver high tensile strength (up to ~1,100 MPa) at a much lower density (~4.5 g/cm³). Engineers evaluate strength-to-weight ratio, yield strength, and fatigue performance to choose materials, especially in aerospace and automotive designs where low mass and high strength are critical.

Conclusion

The strongest metals are defined by a balance of tensile strength, yield strength, heat resistance, and reliability—not a single number. Alloys outperform pure metals by controlling deformation and improving stability, making them essential in aerospace, construction, and medical applications. The “strongest” metal is always the one best matched to real operating conditions.

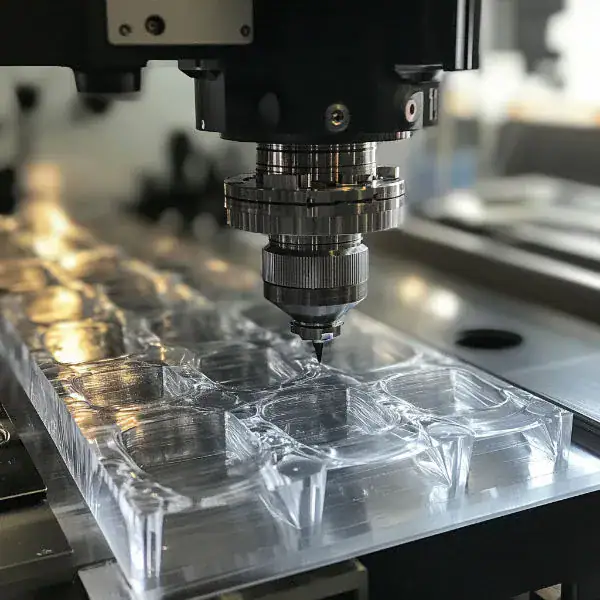

At TiRapid, we help engineers turn material strength into real performance. With deep experience in cnc machining high-strength alloys and tight-tolerance components, we support you from material selection to precision CNC production—ensuring every part is optimized for its actual load, environment, and application.