Precision hole machining is critical for tight-tolerance assemblies. Drilling vs Boring highlights how these two processes differ in accuracy, surface finish, and dimensional control, helping engineers choose the right method and avoid costly errors.

What Is Drilling

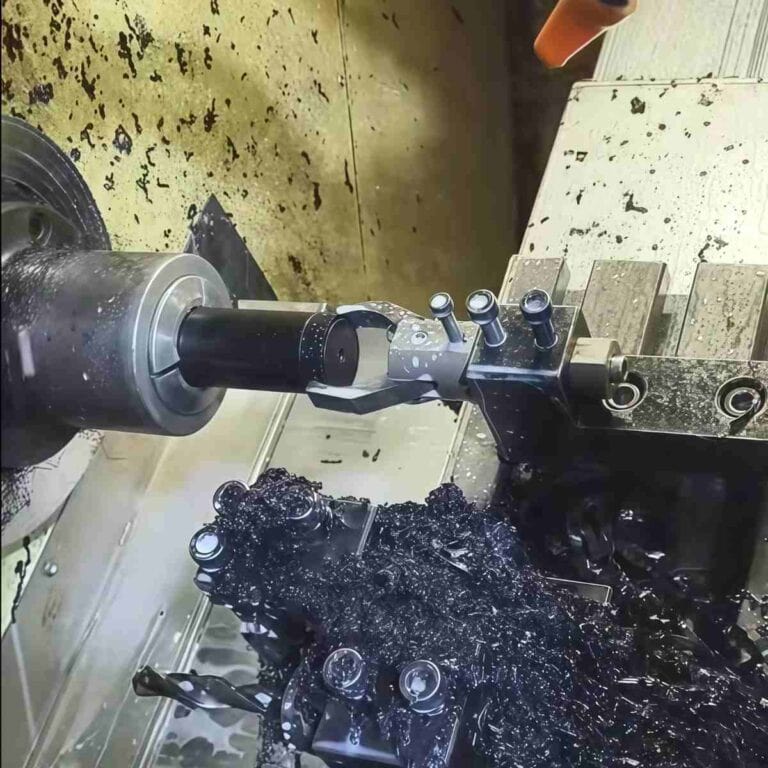

Drilling is the most fundamental hole-making operation in machining. As a core process used by any experienced CNC machining manufacturer, it is applied to quickly create an initial cylindrical hole in a solid workpiece and serves as the foundation for secondary operations such as boring, reaming, or tapping.

Get 20% offf

Your First Order

Basic Definition and Working Principle

Drilling is a machining process that creates a hole by rotating a multi-point cutting tool, typically a twist drill, while applying axial force into the material. Cutting occurs mainly at the drill tip, and chips are evacuated through helical flutes along the tool body.

Speed and Versatility in Hole Creation

Drilling is valued for its speed and adaptability. It can be applied to a wide range of materials, including aluminum, steel, plastics, and composites, making it ideal for high-throughput hole creation where extreme precision is not the primary requirement.

Typical Accuracy and Surface Finish Range

In standard CNC drilling operations, achievable tolerances typically range from ±0.05 to ±0.1 mm, with surface finishes around Ra 3.2–6.3 μm. For tighter requirements, drilling is usually followed by boring or reaming.

Common Drilling Tools and Machines

Common drilling tools include twist drills, center drills, step drills, and spade drills. These tools are widely used on CNC machining centers, drill presses, and CNC lathes with live tooling.

What Is Boring

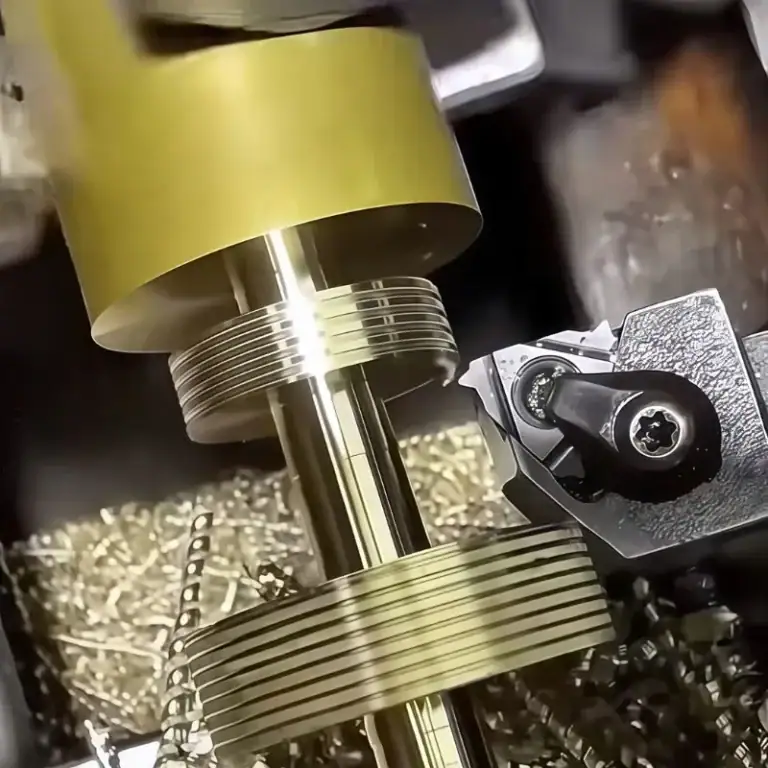

Boring is a precision machining process used to enlarge and refine an existing hole. Unlike drilling, boring focuses on improving hole accuracy, roundness, and alignment, making it essential for tight-tolerance and high-performance applications.

Definition and Core Machining Principle

Boring removes material from the internal surface of a pre-drilled or pre-cast hole using a single-point cutting tool mounted on a boring bar or boring head. The controlled radial cutting action allows precise adjustment of hole diameter.

How Boring Improves Hole Accuracy

Boring corrects common drilling issues such as hole misalignment, ovality, and poor concentricity. Because the cutting diameter can be finely adjusted, boring delivers superior control over final hole size and geometry.

Role of Boring Bars and Boring Heads

Boring bars provide rigidity and stability during cutting, while boring heads allow micrometer-level diameter adjustments. In CNC machining, this combination enables consistent and repeatable precision across multiple parts.

Typical Tolerance and Surface Finish Capability

Boring commonly achieves tolerances of ±0.01 mm or better, with surface finishes around Ra 1.6–3.2 μm. This makes it suitable for applications such as bearing bores, hydraulic cylinders, and engine components.

Drilling vs Boring: Key Differences Explained

Drilling and boring are often confused because both remove material to form holes. In reality, they serve very different roles in precision machining. Understanding their differences is essential for selecting the right process, controlling tolerances, and avoiding unnecessary cost or rework.

Purpose

Drilling is primarily used to create a hole quickly and economically in solid material. Precision is not the main priority.

Boring is performed after drilling to enlarge, correct, and refine an existing hole with high dimensional accuracy.

In practical machining, drilling defines where the hole exists, while boring defines how accurate and functional that hole becomes.

Tooling

Drilling uses multi-point cutting tools such as twist drills, step drills, and spade drills, designed for rapid axial material removal.

Boring relies on single-point tools such as boring bars and adjustable boring heads, which allow precise radial control.

Because only one cutting edge is engaged, boring tools require higher rigidity to prevent vibration and deflection.

Material Removal Method

Drilling removes material aggressively in the axial direction, which makes it fast but less stable.

Boring removes material gradually from the internal wall of an existing hole, allowing precise control of diameter and geometry.

This controlled removal is why boring is preferred for tight tolerances.

Accuracy and Tolerance Capability

Typical drilling tolerance: ±0.05–0.10 mm

Typical boring tolerance: ±0.01 mm or better

For bearing seats, hydraulic bores, or precision alignment features, boring is almost always required.

Surface Finish Quality

Drilling typically produces a surface finish around Ra 3.2–6.3 μm.

Boring can achieve Ra 1.6–3.2 μm with better consistency and roundness.

This makes boring suitable for functional fits and sealing surfaces.

Tool Rigidity and Stability

Drilling tolerates more vibration due to short tool engagement and multiple cutting edges.

Boring demands high system rigidity, especially for deep holes or large diameters, to avoid chatter and taper.

In CNC machining, spindle stability and tool overhang directly affect boring accuracy.

Machining Sequence Requirements

Drilling must occur first to create the initial hole.

Boring cannot be performed without an existing hole and always follows drilling or a hollow casting.

This sequence dependency is a key distinction between the two processes.

Drilling vs Boring Comparison Table

Drilling and boring are both essential hole-making processes in precision machining, but they serve very different purposes. Drilling focuses on speed and material removal to create initial holes, while boring improves accuracy, alignment, and surface finish. Understanding their differences helps engineers select the right process for tolerance, cost, and performance requirements.

Drilling vs Boring Comparison Table

| Aspect | Drilling | Boring |

| Accuracy | Moderate | High |

| Tolerance Range | ±0.1–0.3 mm | ±0.05–0.1 mm |

| Surface Finish | Fair (≈125–250 µin Ra) | Good (≈63–125 µin Ra) |

| Tooling Cost | Low | Medium |

| Machining Time | Fast | Slower |

| Typical Use Cases | Creating initial holes, rough machining | Enlarging holes, improving alignment and roundness |

Drilling vs Boring vs Reaming: Comparison Table

| Process | Drilling | Boring | Reaming |

| Primary Purpose | Create an initial hole quickly | Enlarge and correct an existing hole | Achieve final size and smooth finish |

| Typical Tolerance | ±0.1–0.3 mm | ±0.05–0.1 mm | ±0.005–0.02 mm |

| Surface Finish | Fair | Good | Excellent |

| Tooling | Twist drill | Boring bar / boring head | Reamer |

| Hole Path Correction | No | Yes | No |

| Position in Machining Sequence | First | After drilling | Final operation |

Tooling and Setup Requirements

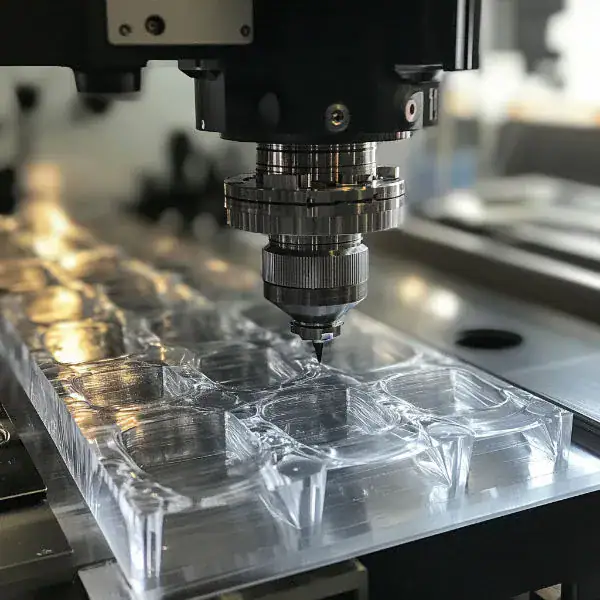

Tool selection and setup quality directly determine hole accuracy, surface finish, and process stability. Drilling and boring use different cutting mechanics, so understanding tooling rigidity, holder selection, and alignment control is essential to achieve consistent results in precision hole machining.

Drilling Tool Overview

Drilling tools are designed for fast material removal and hole initiation, but their structure limits achievable precision.

Drill bit structure and rigidity

Twist drills are multi-point cutters with flutes for chip evacuation. Rigidity decreases as diameter increases or length-to-diameter ratio grows, making deep holes more prone to deflection.

Tool wear and runout impact

Worn cutting edges and spindle runout cause oversized holes, poor roundness, and rough surface finish. Even small runout can significantly affect hole quality at higher spindle speeds.

Common drilling tools include HSS, cobalt, carbide-tipped, and solid carbide drills, used on CNC mills, lathes, and drill presses

Boring Tool Overview

Boring tools are designed to refine and correct existing holes with higher accuracy and control.

Boring bar vs boring head

Boring bars are single-point cutters used for diameter enlargement and alignment correction. Boring heads allow fine diameter adjustment, making them ideal for tight tolerance control.

Tool holder influence on accuracy

Rigid holders and balanced tool assemblies reduce vibration and chatter. For deep holes, vibration-dampened boring bars are critical to maintain concentricity and surface quality.

Compared to drilling, boring offers superior control over diameter, roundness, and location.

Setup and Alignment Considerations

Proper setup is essential for preserving tolerances and surface finish across drilling and boring operations.

Concentricity and runout control

Minimize tool and spindle runout using precision collets, balanced holders, and verified tool offsets to avoid uneven cutting.

Machine rigidity and fixturing

Secure fixturing and rigid machine structures prevent deflection and vibration, which directly impact hole accuracy.

Additional best practices include matching spindle speed and feed rate to material, applying proper coolant for heat and chip control, using pilot holes before boring or reaming, and monitoring tool wear throughout production runs.

Tolerances and Surface Finish Considerations

Hole tolerances and surface finish directly affect part fit, performance, and interchangeability. Drilling and boring deliver different accuracy levels, and understanding their limitations helps engineers choose the right process without unnecessary cost or rework.

Typical Drilling Tolerance Limits

Drilling is primarily a hole-creation process rather than a precision finishing operation. In most CNC machining applications, drilled holes typically achieve tolerances of ±0.1–0.3 mm, with surface finishes around Ra 3.2–6.3 μm.

In real production, factors such as drill runout, tool wear, chip evacuation, and material hardness often introduce slight diameter variation or ovality. For clearance holes or non-critical features, this level of accuracy is usually acceptable.

How Boring Refines Size and Geometry

Boring is used to enlarge and correct an existing hole. By removing material gradually with a single-point cutting tool, boring significantly improves diameter accuracy, roundness, concentricity, and alignment.

In practice, boring commonly achieves tolerances of ±0.02–0.05 mm, with surface finishes around Ra 1.6–3.2 μm. From experience, boring is essential when holes must precisely align with shafts, bearings, or mating components.

When Drilling Alone Is Insufficient

Drilling alone becomes insufficient when tight fits, smooth sealing surfaces, or high positional accuracy are required. Typical examples include bearing seats, hydraulic components, precision housings, and dowel pin holes.

In many machining projects, skipping boring to save time often leads to assembly issues, uneven wear, noise, or reduced service life—especially in rotating or load-bearing systems.

Recommended Approach

Use drilling for fast hole creation and general-purpose features

Apply boring when tighter tolerances or improved hole geometry are required

Reserve additional finishing operations only when specified by functional or fit requirements

Design for Manufacturability (DFM) in Hole Machining

DFM in hole machining focuses on designing holes that are easy to drill or bore while meeting functional requirements. Good DFM reduces machining time, cost, and unnecessary precision.

Designing Holes for Drilling Efficiency

Drilling is most efficient for simple holes with moderate tolerances.

Keep depth within 10–12× drill diameter

Prefer through-holes over blind holes

Use standard drill sizes

Avoid tight tolerances unless function requires them

When to Specify Boring on Drawings

Specify boring when drilling alone cannot meet requirements.

Tolerance tighter than ±0.05 mm

Critical alignment, roundness, or concentricity

Bearing, shaft, or sealing interfaces

Cost vs Precision Trade-Offs

Higher precision increases cost.

Use drilling for non-critical holes

Apply boring only to functional holes

Avoid over-specifying tight tolerances

Recommended Practice

Design holes for drilling by default, and use boring only where precision truly matters.

Common Applications by Industry

Hole machining requirements vary by industry. Drilling is typically used for fast hole creation, while boring and reaming are selected when alignment, tolerance, and surface finish directly impact performance, safety, or assembly accuracy.

Aerospace Precision Hole Machining

Bearing seats, hydraulic ports, actuator mounts

Tight tolerances and concentricity requirements

Boring and reaming used to ensure alignment and fatigue resistance

Automotive and Transmission Components

Engine blocks, valve guides, gearbox housings

Drilling for rough holes, boring for size control

Reaming applied to press-fit pins and shafts

Industrial Machinery and Tooling

Bushing seats, alignment holes, fluid ports

Boring corrects cast or drilled hole distortion

Emphasis on repeatability and assembly accuracy

Precision and Micro-Machining Scenarios

Sensor housings, medical components, micro-mechanisms

Small diameters with strict tolerance control

Fine boring or reaming required for consistency

What’s the Best Hole Machining Method for Tight Tolerances

Selecting the right hole machining method is critical when tolerances, alignment, and fit directly affect part function. Drilling, boring, and reaming each play a distinct role in achieving dimensional accuracy and repeatability.

Drill-only vs. Drill + Boring

Drill-only: suitable for clearance holes and loose tolerances (±0.1–0.3 mm)

Drill + boring: required when diameter accuracy, roundness, or concentricity matters

When Boring Is Mandatory

Bearing seats, press-fit holes, and alignment-critical assemblies

Large diameters or holes affected by casting or drilling distortion

Practical Engineering Recommendations

Use drilling to create the hole quickly

Apply boring to correct geometry and size

Add reaming only if ISO H7–H8 or smoother finishes are required

FAQs

What Are The Advantages Of Boring Over Drilling?

Boring offers much higher accuracy than drilling. In the boring process, I can correct hole position, roundness, and concentricity, typically reaching ±0.05 mm or better. This is the key advantage in boring vs drilling, especially when comparing a boring bit vs drill bit for precision work.

Is Drill Boring The Same As Using A Boring Tool?

No. Drill boring is often a misuse of terms. A drill bit is designed to create an initial hole, while the boring process refines an existing hole. This highlights the difference between boring and drilling in real CNC applications.

What Is The Difference Between Boring And Drilling Machine?

The difference between drilling and boring is not the machine, but the operation. I often use the same CNC mill or lathe, switching tools and strategies. Drilling prioritizes speed, while boring focuses on accuracy and geometry control.

What Are The Three Types Of Drilling?

The three common drilling types are center drilling, standard drilling, and deep-hole drilling. All are used for fast hole creation, but none replace boring when tight tolerances are required in boring vs drilling decisions.

What Are Examples Of Boring Tools Compared To Drill Bits?

Typical boring tools include boring bars, boring heads, and fine-adjust boring systems. Compared to a drill bit, these single-point tools allow precise diameter control, clearly showing the difference between drilling and boring.

Can You Bore With A Drill Bit?

No. You cannot achieve true boring with a drill bit. A drill lacks radial control and cannot correct geometry. True boring requires a dedicated boring tool, not a drill boring approach.

What Type Of Tool Is A Drill?

A drill is a multi-point cutting tool designed for axial material removal. It is fundamentally different from boring tools and also differs from milling cutters, which explains the difference between drilling and milling.

Is Drilling A Hard Job Compared To Boring?

Basic drilling is easy, but precision drilling is difficult. Tool runout, heat, and chip evacuation limit accuracy. In many cases, I rely on boring after drilling to achieve reliable results, reinforcing the practical difference between drilling and boring.

Conclusion

Drilling and boring serve different but complementary roles in precision hole machining. Drilling creates holes efficiently, while boring refines accuracy, alignment, and surface quality. Choosing the right process based on tolerance, function, and cost ensures reliable assemblies, longer service life, and fewer manufacturing risks.

At TiRapid, we combine high-speed drilling with precision boring to achieve tight tolerances and stable alignment. Serving automation, medical, and industrial clients, we ensure quality, consistency, and on-time delivery. Send us your drawings for expert review.